森田 子龍/Morita Shiryu

書家の森田子龍(1912~1998)は、第二次世界大戦後に一時代を築いた革新的な書表現の試みである、「前衛書」の旗手として世界的に知られています。

兵庫県豊岡市に生まれた森田は、中学校を卒業して働くかたわら、1932年頃から書を手がけるようになり、神戸の書の研究会で書家の上田桑鳩(そうきゅう、1899~1968)と出会います。戦前に書道藝術社を結成するなど、「前衛書」の端緒となる運動をすでに行っていた上田の知遇を得て、1937年に上京すると機関誌『書道藝術』の編集に携わり、展覧会への出品を始めました。同年に第2回大日本書道院展にて推薦金賞、特選銀賞第一席を受賞し、さらにその翌年には日満支書道展において文部大臣賞を獲得するなど、華々しいデビューを飾っています。

1948年には、疎開のために戻っていた故郷で、上田門下の機関紙である『書の美』を創刊しました。この雑誌において、文字を書かない実験的な書を研究する「α部(アルファぶ)」が新設され、その公募作品の選評を画家の長谷川三郎(1906~1957)が担当したほか、朝日新聞社の学芸部記者で「現代美術懇談会(以下、ゲンビ)」の発足に一役買った村松寛(1912~1988)や、洋画家の須田剋太(1906~1990)らが寄稿している点などに、戦後の書と美術の交流を実現させた功績が窺えます。

1950年代には日展をはじめとした展覧会において保守的な書家と革新的な書家のあいだに軋轢が生じていましたが、そうした潮流を受けて森田も自身の先鋭性を強めていきます。1951年に芸術総合誌『墨美(ぼくび)』を創刊したことを皮切りに、その翌年は上田のもとを離れて井上有一(1916~1985)らと墨人会の設立、さらに相互批評や研鑽を目的とした『墨人』の創刊にも従事するなど、八面六臂の活躍を見せました。たとえば『墨美』の創刊号の表紙に、当時の日本ではまだ無名だったアメリカの画家、フランツ・クライン(1910~1962)の絵を採用し、『墨人』を通して吉原治良(1905~1972)たちゲンビのメンバーと交流を深めるなど、森田の活動は書と国内外の抽象画家たちを結びつけるとともに、森田自身が海外でも認知される契機を生みました。また、明治以降の書の歴史化やデータベース化によって、日本の近代美術において周縁化されている書を芸術として確立させようとした点も見逃せません。森田は芸術家としてのみならず、編集者としても優れた才能を持ち合わせていたのです。

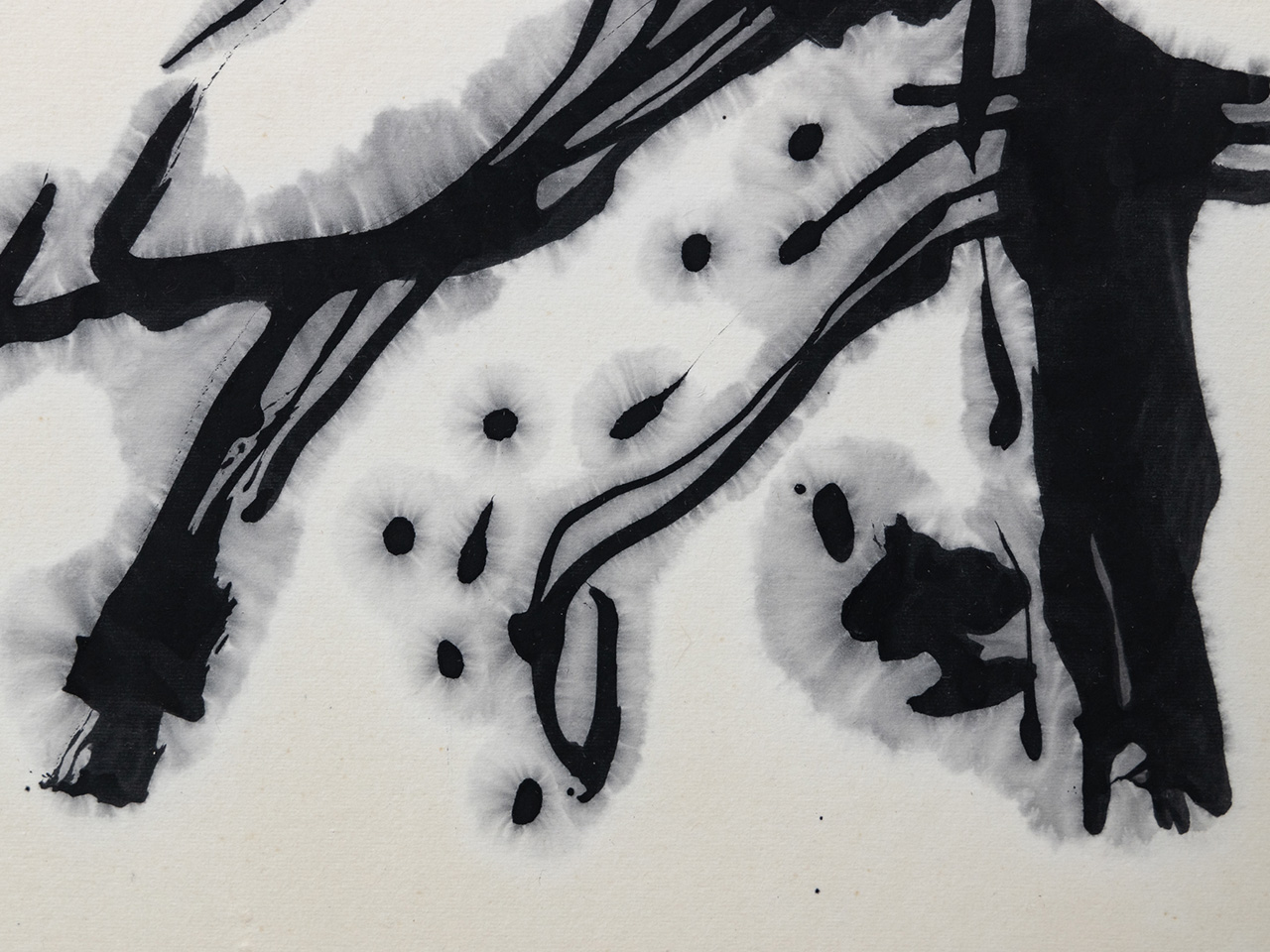

そんな森田の手がけた作品では、字形にとらわれない躍動感があふれつつ、あくまでも絵ではなく文字として表現されている点もさることながら、表面に残された筆の跡によって時間の経過や身体の動きが視覚化されている作風も特筆すべきでしょう。【蒼】(1954年)における、濃度の高い墨が盛り上がり生み出された凹凸、【圓】(1969年)の、にじみと平面的な線が見せる筆の運びなど、様々な方法を通して独自の造形を模索しています。黒いケント紙にアルミ粉を混ぜたボンドで書いたものに、上から漆をかける独自の技法「漆金」を作りだすなど、新しい素材の探究にも余念がありませんでした。そのようにして紙の上にしっかりと刻まれた筆跡は、作者の息づかいや精神、その一度きりの生命の輝きを鮮やかなまでに浮かび上がらせています。

Calligrapher Shiryu Morita (1912-1998) is globally recognized as a pioneer of “Avant-garde Calligraphy”, an innovative movement in expressive calligraphy that defined an era after World War II.

Born in Toyooka, Hyogo Prefecture, Morita began pursuing calligraphy around 1932 while working after graduating from junior high school. In Kobe, he joined a calligraphy study group, where he encountered Sokyu Ueda (1899-1968), a calligrapher who had already initiated movements that laid the groundwork for avant-garde calligraphy, including the formation of the Shodo Geijutsu Sha (Calligraphy Art Society) before the war. Through his connection with Ueda, Morita moved to Tokyo in 1937, contributed to editing the journal Shodo Geijutsu, and began exhibiting his works. That year, he made a brilliant debut, winning the Recommendation Gold Prize and the Special Silver Prize First Seat at the 2nd All Japan Calligraphy Institute Exhibition. The following year, he secured the Minister of Education Award at the Japan-Manchuria-China Calligraphy Exhibition.

In 1948, after returning to his hometown during the war’s evacuation, Morita launched the journal Sho no Bi (The Beauty of Calligraphy), the official journal of Ueda’s circle.The journal introduced an experimental section called the “Alpha Division”, dedicated to exploring calligraphy without traditional characters. Painter Saburo Hasegawa (1906-1957) evaluated submissions, while contributors included Hiroshi Muramatsu (1912-1988), a journalist from Asahi Shimbun who helped establish the Contemporary Art Discussion Group (Genbi), and Western-style painter Kokuta Suda (1906-1990). This collaboration reflects the achievement of realizing postwar interaction between calligraphy and art.

In the 1950s, tensions arose between conservative and avant-garde calligraphers in exhibitions like the Nitten (Japan Fine Arts Exhibition). Amidst this movement, Morita embraced a more radical approach. In 1951, he founded the interdisciplinary art magazine Bokubi (The Beauty of Ink). The following year, he parted ways with Ueda and established the Bokujin-kai (Ink People Association) with Yuichi Inoue (1916-1985) and others. He also launched the magazine Bokujin, aiming to foster mutual critique and artistic refinement. Demonstrating remarkable versatility, he engaged in a wide range of activities with tireless dedication. For instance, the inaugural issue of Bokubi featured a cover painting by Franz Kline (1910-1962), then little-known in Japan. Through Bokujin, Morita strengthened ties with members of the Gutai Art Association (Genbi), such as Jiro Yoshihara (1905-1972), linking calligraphy with abstract artists both domestically and internationally. His initiatives also helped elevate calligraphy as an art form by creating historical records and databases, challenging its marginalization in modern Japanese art. Morita was not only an outstanding artist but also a highly talented editor. Morita’s works are characterized by a sense of dynamism that transcends conventional letterforms, while firmly maintaining their identity as calligraphy rather than mere images. His brushwork, with strokes left visible on the surface, vividly visualizes the passage of time and physical movement, an aspect that is particularly noteworthy. In Ao (Deep Blue) (1954), dense ink forms textured ridges, while in En (Circle) (1969), bleeding effects and planar lines reveal intricate brush dynamics, showcasing his exploration of unique forms through various techniques. Morita also developed his original technique, Shikkin (lacquer and gold), in which he wrote on black Kent paper using an adhesive mixed with aluminum powder, then finished it with lacquer. He was deeply engaged in exploring new materials. The firmly inscribed brushstrokes on paper vividly reveal the very breath of the artist, his spirit, and the fleeting radiance of a singular moment in life.

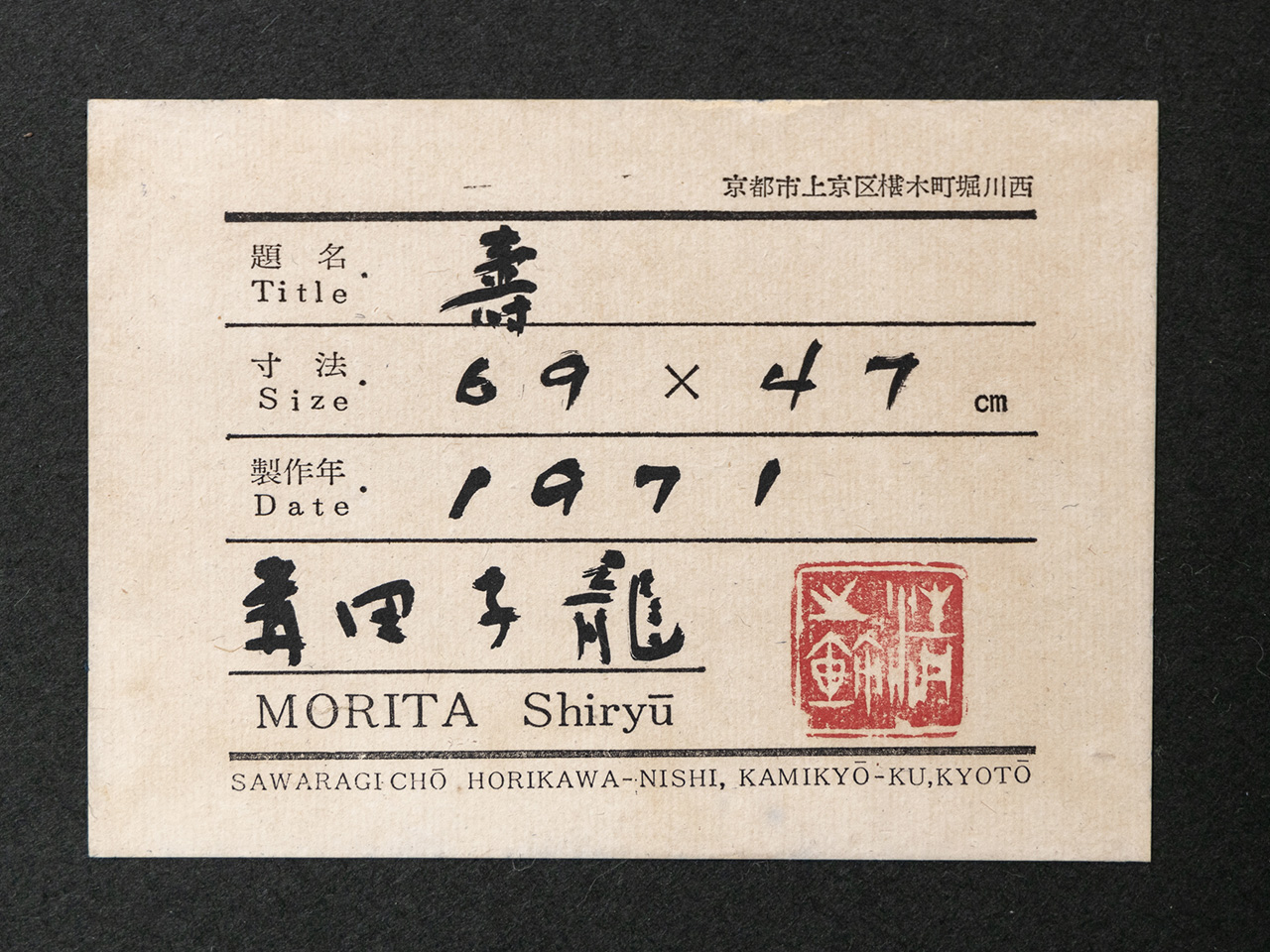

作品名:寿(書)

サイズ:69×47cm(1971年 紙に墨 共シール)

価格:SOLD OUT

価格は税抜き表示です