能楽

能について

室町時代に成立した能は、600年以上の長きにわたって発展してきた、日本を代表する古典芸能です。起源を同じくする狂言が、ほとんど能面を用いないセリフ中心の喜劇であるのに対し、能は、主にシテ(主人公)が能面をつけ、歌と楽器に合わせて演じる歌舞劇です。人間が心の内に抱える悲しみや苦しみ、懐旧や恋慕の情が、簡素化された動きによって静かに表現されています。登場人物の多くが、幽霊や鬼、妖怪、神など、この世のものならざる存在であることも特徴です。

About Noh

Noh, which originated in the Muromachi period, has developed over more than 600 years to become a representative classical performing art of Japan. While sharing the same origins, Kyogen, which is mainly comedic with minimal use of masks and focused on dialogue, contrasts with Noh, where the Shite (the main character) wears masks and performs in a sung and instrumental drama. Noh quietly expresses the sadness, suffering, nostalgia, and love hidden within human hearts through simplified movements. Another characteristic is that many characters are otherworldly beings such as ghosts, demons, monsters, or gods.

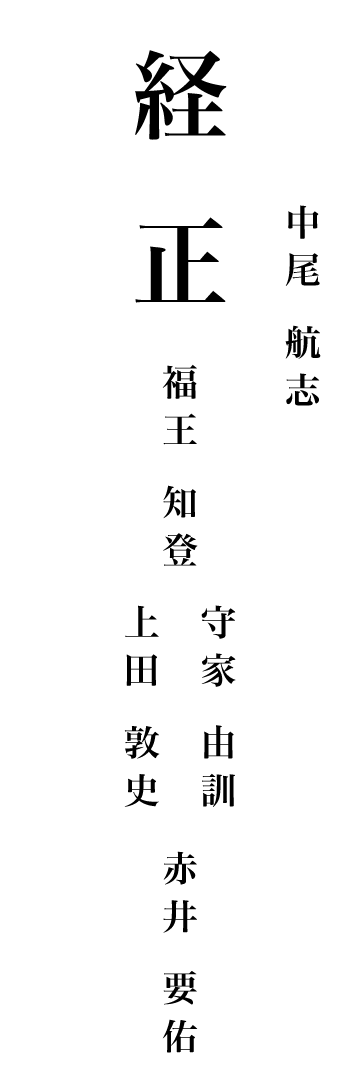

経政/経正について*

能の演目の一つである「経政/経正」は、『平家物語』に材をとった修羅能です。和歌と琵琶に秀でた武将・平経政の霊がシテとして、仁和寺の僧都行慶(そうずぎょうけい)がワキ(シテの演技を引き出す相手役)として登場します。 守覚法親王(しゅかくほっしんのう)から、平経政の霊を弔うよう仰せつかった行慶は、経政が生前に愛用していた琵琶「青山(せいざん)」を仏前に供え、管絃講(楽器を奏でて死者を弔う法事)を催します。そうして夜も更けた頃、弔いをありがたく思った経政の霊が灯火の陰に現れます。その姿は夢幻のようにおぼろげではっきりとは見えないものの、行慶は聞こえてくる亡霊の声に耳を傾け、言葉を交わします。詩歌や音楽に親しんだ日々を思いだすうちに懐かしさがこみあげた経政は、手向けられた「青山」を手に取り、それを奏で舞いながら、楽しいひとときを過ごしました。しかし、その時間も長くは続かず、突然修羅の苦しみに襲われた経政は、そのあさましい姿が人々に見られることを恥じ、灯火を吹き消すとともに、自身も夜の闇に紛れて消え去ってしまうのでした。 登場人物がシテとワキの二人のみという珍しさに加え、前場(まえば)と後場(のちば)でシテが変身する形式の多い修羅能のなかで、一場物の劇的な構成をとっている点も特殊な演目です。また、修羅能でありながら、優雅な歌や舞によって、平家の貴公子の心の内を詩情豊かに描きだした本作は、小品ながらも洗練された佳作と言えます。

*宝生/金春/喜多流では「経政」と表記。観世/金剛流は「経正」と表記します。

About Tsunemasa

One of the Noh plays, Tsunemasa is a warrior play based on the “Tale of the Heike”. The spirit of the warrior Tsunemasa Taira, skilled in waka poetry and biwa (Japanese lute), appears as the Shite, with the monk Gyokei, the abbot of Ninna-ji Temple, as the Waki (the supporting actor who interacts with the Shite). Gyokei, who was asked by Shukaku Hosshin-nou (monk from the Imperial Family) to mourn the spirit of Tsunemasa Taira, he offered Tsunemasa’s beloved biwa called “Seizan” before the Buddha and conducted a kangenko (a Buddhist ceremony to mourn the deceased by playing a musical instrument). As the night deepens, the spirit of Tsunemasa, feeling grateful for the offering, appears in the shadow of the lamp. Although the figure is as dim and indistinct as a dream vision, Gyokei listens to the voice of the ghost, and he exchanges words with it. Remembering the days of poetry and music, Tsunemasa feels nostalgia welling up within him. Taking the offered “Seizan” in hand, he plays and dances, enjoying a brief moment of happiness. But that time was short, for suddenly, struck by the agony of Shura, and ashamed to be seen by others, he blew out the lamps and disappeared into the darkness of the night. In addition to the rarity of having only two characters, Shite and Waki, it is also unique in that it is a dramatic one-act play, unlike most Shura Noh plays in which the Shite transforms between the Maeba (first half) and Nochiba (second half) stages. Despite being a Shura Noh play, this piece elegantly portrays the inner emotions of a noble youth of the Heike family through graceful songs and dances, making it a refined masterpiece.

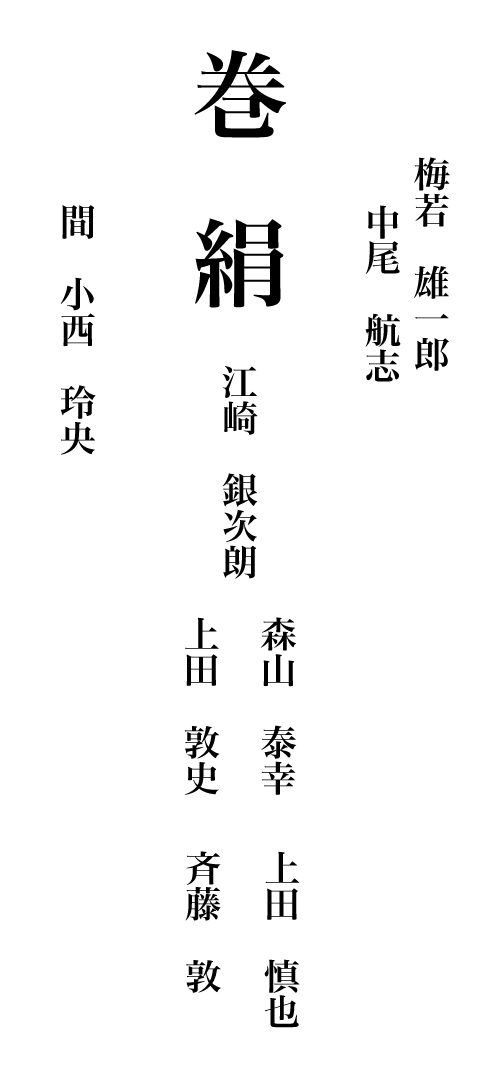

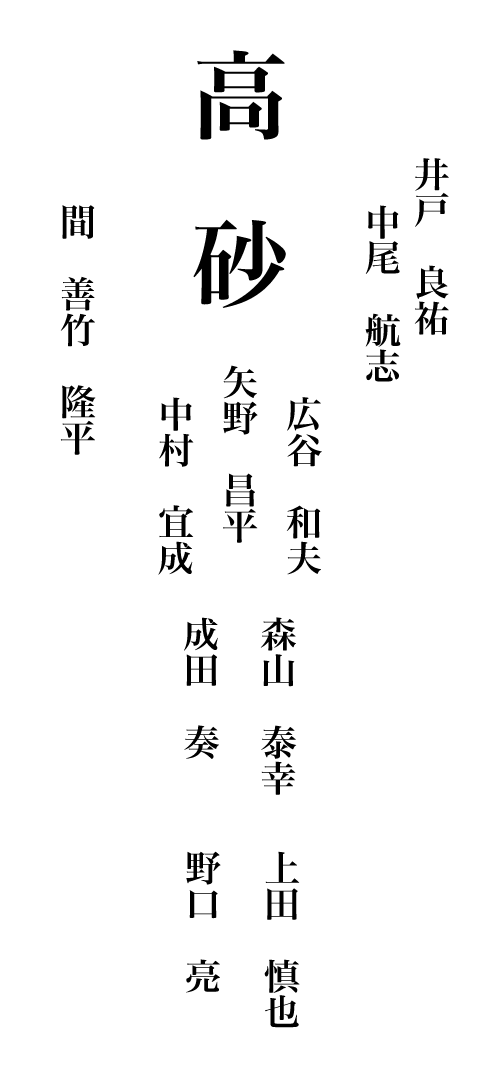

奉納舞謡会 梅春会 秋の大会(令和5年10月22日/於:三輪山会館)

喜寿記念 梅春会 秋の大会(令和6年11月24日/於:大槻能楽堂)

梅春会 秋の大会(令和7年10月26日/於:山本能楽堂)